Day Book

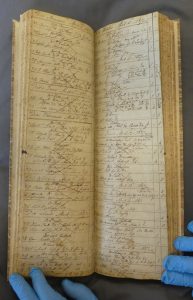

Like all good businesses John recorded his shop sales in a ledger, and luckily for us his Day Book ledger listing credit sales between 9th August 1825 and 23rd September 1829 has survived and is now owned by the Science Museum.

The Day Book measures approximately 422 mm by 140 mm wide and 30 mm thick. It is bound in a stout cover of brown cardboard, originally covered with marbled paper, and has almost certainly been re-bound at some time. Inside, the 272 pages are not numbered but are paper water-marked “T. Edmonds, 1823”. All the handwritten entries are crossed through as Walker posted them into his ledger, and many are also ticked in red ink. Each new day is titled in Latin (e.g. Die Martis, August 9th 1825) followed by the credit sales entries made on that day of the simple remedies then in use as well as 168 sales of Friction Lights.

The Day Book was donated to the Science Museum by Bryant & May in 1937. It was acquired by them in 1927 from John William Ethelbert Price who by then was proprietor of Messrs Hardcastle & Sons, one of Walker’s rival chemists in Stockton.

Note : the photographs on this web page were take on 9th June 2023 at the Science Museum Archive in Wroughton and are reproduced here under licence from the Science Museum.

First recorded sale of Friction Matches

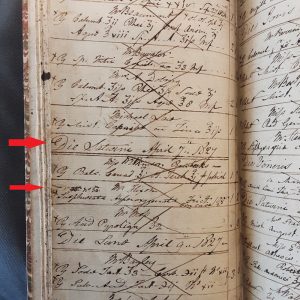

This surviving Day Book contains written proof in Walker’s handwriting of the first recorded sale of Friction Matches :

- It was a sale of 100 Sulphurata Hyperoxygenata Friction costing 1 shilling plus 2d for a tin case to hold them to a Stockton Solicitor Mr. (John) Hixon on the 7th April 1827, recorded as Sale No. 30

However, there is a mystery about the numbering of this famous Day Book entry. A person other than John (perhaps his shop assistant as it is in different handwriting) wrote 36th, realised it was a mistake, tried to change the 6 to a 0 but as it did not look right crossed out the number 36th with three lines through it and wrote No. 30. The next sales entry on the page shows how John wrote the number 3. He was a qualified physician and wrote his entries in Latin. Perhaps he told his assistant to write this number in for him and they made a mistake but where did the number 36 come from? There is a possibility John had thought it was the 36th but realised his mistake later after checking his notebooks.

This entry is now interpreted by historians as meaning there were a previous 29 of either unrecorded sales and /or of those he gave away on a trial basis as part of the market research, or that this was batch No. 30 of his Friction Match experiments and hence the discovery was deduced to be sometime in 1826 when he began experimenting with percussion powders.

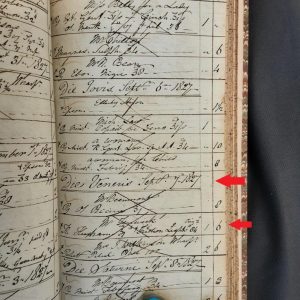

John started using the name “Friction Lights” for his matches from a sale on 7th September 1827, but kept secret the composition of the chemicals used in his match.

Sometime in 1827 or 1828, in Thomas Jennett’s print shop at 58 High Street his employee John Ellis (age 66, a bookbinder in the 1841 Census) made the world’s first paste board matchbox container for John Walker to hold his Friction Lights. This replaced the original but expensive 2d tin case John had sold to John Hixon. There is no evidence these paper-based paste board match containers, or the tin cases originally used had a paper label stuck on them and a ‘John Walker Friction Lights’ label is not thought to exist. Perhaps John would rather write in a quill pen on the paste board containers what was inside them. However, there may have been a paper label stuck on the tin case to say what was inside and again it would possibly have been written by John himself, but none are known to be in existence.

Scientific recognition of Walker’s invention

The first ever public mention of John Walker’s invention was published in 1830 in the prestigious ‘Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature and Art’ for July-December 1829 under the title “Instantaneous Light Apparatus‘. This scientific journal was to a large extent a vehicle for authors associated with the Royal Institution, who took it over in 1830 and it then appeared as the ‘Journal of the Royal Institution’ from 1832. The 1830 entry read :

- “Amongst the different methods invented in latter times for obtaining light instantly, ought certainly to be recorded that of Mr Walker, chemist, Stockton-upon-Tees. He supplies the purchaser with prepared matches, which are put up in tin boxes, but are not liable to change in the atmosphere, and also with a piece of fine glass-paper folded in two. Even a strong blow will not inflame the matches, because of the softness of the wood underneath, nor does rubbing upon wood or any common substance produce any effect except that of spoiling the match ; but when one is pinched between the folds of the glass-paper, and suddenly drawn out, it is instantly inflamed. Mr. Walker does not make them for extensive sale, but only to supply the small demand that can be made personally to him”.

When John Walker died in May 1859 many national British newspapers carried ‘glowing’ obituaries usually mentioning an association between Walker and Michael Faraday, which is attributed to the Journal of 1829 and Michael Faraday’s connections with The Royal Institution. However, there is no evidence to show that Faraday ever met or corresponded with John Walker.

Day Book discovered in 1890s

There was a very fortunate event in the John Walker story when his Day Book was discovered by Stockton hairdresser, artist and historian Joseph Parrott in the early 1890’s. He claims to have found it discarded in a pile of pharmaceutical rubbish thrown out from William Hardcastle’s chemist shop in Finkle Street, Stockton.

It is also interesting to note that William Hardcastle bought Friction Lights from John Walker on 28th November 1827. Also, we know many people associated with the Stockton & Darlington Railway Company subsequently visited and bought medication and Friction Lights from John Walker’s shop and perhaps they used them to fire up the engine boilers.

The journey of the Day Book

The journey of the Day Book from John Walker’s shop to its current home in the Science Museum is a long and fascinating one :

- Hardcastle & Sons were Walker’s rivals in business in Stockton and would have acquired all his artefacts, including the Day Book and all his stock of chemicals, when Walker retired in 1858. Hardcastle’s shop was in Finkle Street, Stockton

- In August 1880 William Hardcastle wrote a letter to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle after the newspaper had made an enquiry about the invention of the friction match. In the letter Hardcastle said that he had in his possession John Walker’s Day Book ledger along with other unspecified goods and articles in the ‘stock and effects’ of John Walker which he had bought in 1858 when Walker had retired. Hardcastle described an entry in the Day Book of April 7th 1827 and put forward a claim for Walker as the inventor of the Friction Match and not Isaac Holden a woollens manufacturer who had invented something similar in 1829

- In the early 1890’s, apparently there was a pile of rubbish outside Hardcastle’s shop ready to be thrown out, and fortuitously a local Stockton hairdresser Joseph Parrott realised its importance and ‘rediscovered’ it. Joseph Parrott gave a series of lectures in Stockton in the 1890’s, reported in the newspapers at the time, on the various ways of obtaining fire and light throughout the centuries as well as also talking about and championing John Walker as the inventor of the Friction Match

- in 1896 Joseph Parrott sent the Day Book and eight of Walker’s Matches to a fellow Stocktonian Professor Bone of Owens College in Manchester for analysis. However, Professor Bone’s analysis didn’t appear until 1927, in Nature magazine, 100 years after Walker’s first sale

- in 1891 William Hardcastle took on his friend John William Price into the Hardcastle chemist business as an errand boy. In the 1901 census Price was now a “Chemist Drug Assistant”. William Hardcastle married Sarah Ann Robinson in Stockton in 1903 but he died in 1907 aged 60 with no children, It was probably at this sad time that Price was asked by Mrs Hardcastle to run the business for her

- Price traded under the Hardcastle name and kept the interior and contents of the shop as they had been in the late 19th Century, amongst which was John Walker’s stock. It is not clear how Price became the full owner of Hardcastle’s chemist shop. In the 1911 census Price, aged 33, classed himself as “working on Own Account” but he worked there until 1962

-

1909 booklet, edited by Michael Heavisides By 1909 the Day Book was back in the possession of the Hardcastle family. It is not known when and whether they were given it or if they purchased it from Joseph Parrott but Mrs William Hardcastle kindly lent the Day Book and Walker’s Pestles and Mortars to Michael Heavisides for his 1909 book ‘The True History of the Invention of the Lucifer Match by John Walker of Stockton-on-Tees’ which includes a photograph of the April 7th 1827 entry of the first recorded sale and a photograph of the Pestles and Mortars

- On 17th March 1927 John William Price appeared at Stockton Bankruptcy Court with a debt of £314. His assets included three pestles and mortars used by John Walker and his Day Book. Price said they were valued at £120 but it was his opinion would raise £1,000 if they were sold at Christie’s Auction House. The (Court) Official Receiver did not agree with his valuation and said Messrs. Bryant & May had already offered £300 for them. Price said that the artefacts had been in his possession but his creditors now held them as security

- Records show that Bryant & May acquired the Day Book and the Pestles and Mortars in 1927, and it is reasonable to assume that they paid £314 for them which would have cleared John Price’s debt

- The Day Book and Pestles and Mortars were donated by Bryant & May to the Science Museum by Bryant & May in 1937

- When Price retired in 1962, some of the Hardcastle shop stock was given to Beamish Open Air Museum via Frank Atkinson who at the time was the curator at Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. However there was no record kept of what was Walker’s stock, if there was any at all

In 1995 the Day Book was back in Stockton, on display in The Green Dragon Museum from 14 October to 23 November, as part of the British Matchbox Label and Bookmatch Society’s 50th Anniversary Celebrations. It was briefly back home and not far from John Walker’s shop at 59, High Street, before it was returned to the Science Museum.